Remember old Sergeant Joe Friday (played by Jack Webb) of Dragnet? He was famous for saying to a witness, “All we want are the facts, ma’am!” Joe the detective, like Jeff the historian, is after the facts. While historians reflect on things like causation—why was Archduke Ferdinand murdered and was his death the contributing factor to the beginning of World War 1?—the facts of the story are of primary importance for the historian because, without them, the interpretation of the events will suffer.

Last week, shortly after I published my essay on MLK Jr., I was alerted to an error in my post by a keen-eyed reader. I wrote that King was murdered in Montgomery, AL, when he was actually murdered in Memphis, TN. I immediately corrected the error on the blog but not before the essay was forwarded to my list of readers. Ugh!!! How did that happen? Talk about a major blunder! There are two major issues that writers seek to avoid—plagiarism, using another’s work improperly; and errors, misstating the details. I committed the latter.

Just how this mistake crept into my prose, I am not quite sure. I had written an entry on MLK Jr. for a new dictionary of Christian history that I am contributing to and, somehow, I made that error in the essay. Did I copy the error from one of my sources? Or did I just get confused in my mind with events in King’s life that happened in Montgomery vs. what happened in Memphis. I am not what you would call a “King scholar,” but his life does create a certain fascination for me, particularly as I have worked on Baptists and race. I had the opportunity to visit the MLK site in Atlanta a few years ago and tour the church. Very important landmarks. But I’ve never been to Memphis (or Montgomery for that matter). I’m sure there are equally important landmarks in those places that highlight the King story. I know that the Lorraine Motel is one such place.

Getting the facts wrong is easy to do, especially for historians. Facts are our burden, our stock and trade. Ferreting out the fine details of a story is part of our craft. Coming up with corrections in the historical record is part of what we do. In some sense, we are always trying to set the record straight, especially in our own writing. No one wants to put something in print that is later proven to be factually in error. Mistakes do happen, hopefully to others but to me? Yea, they even happen with me. Unfortunately.

As historians, we remember when we discover through reading the significant factual errors in another writer’s work. It happens to the best of us. A number of years ago, I was asked to write an essay on Squire Boone, the brother of the legendary Daniel Boone. I was told he was an important Kentucky Baptist. Would I write a biographical essay on his life? Sure. I was sent a box of material that the editor of the series the essay was to be published in had collected on Boone and began my work. Writing on the Boone family is challenging. Daniel Boone is an important figure in American history and there’s a society of Boone descendants that keeps his memories alive. As I began to assemble a narrative on Squire, I learned that the father of Daniel and Squire was a Squire also as was a nephew, the son of a different brother of Daniel. I would eventually learn that there are no less than thirty-two Squires in the Boone genealogy. Keeping them straight was a challenge. To complicate matters, the nephew Squire was a Baptist. Anyway, I eventually wrote an essay that Kentucky Baptist history had wrongly considered Squire, the brother of Daniel, an early Baptist preacher in the state. I argued that the uncle and the nephew had their stories conflated in the historical record. Once one historian of note confused the two, later historians repeated the error, or so I surmised. You’d have to read the essay to see the evidence, but I made a pretty good case for correcting KY Baptist history.

Another error I discovered was in a book that attributed Strong’s Concordance to the Baptist Augustus Hopkins Strong rather than to the Methodist James Strong. It was a surprising error and easily corrected. Not I’m sure how or why my brother historian made the error, but made it he did. Generally, to correct errors such as these, authors need informed readers to read the work and point out the errors to their authors before they are printed. This is often the role of editors and outside readers. Or perhaps some other friend or colleague may be invited to read the text and will note the mistake. I appreciate the brother who alerted me to my error.

So why do errors creep into texts of even trained, careful historians? Let me suggest several reasons why I have seen errors in my own writing and that of others. First a historian is only as good as his sources. Sometimes the sources themselves contain errors and sometimes they are merely vague or spotty and the historian makes a judgment as to proper conclusions. In today’s internet world, access to a diversity of sources offers a much greater opportunity to cross check facts and compare details. Sources that were inaccessible to the researcher without travel or depending on interlibrary loan, can now be located through a variety of online websites—Google Books, Archive.org or HathiTrust.org—plus any number of narrow collections on particular topics. The quality of research today has been significantly improved from just a quarter of a century ago.

In the case of the location of the MLK murder, there is a plethora of material online that specifically notes the location of the sad act. There is even a museum located at the Lorraine Motel, which obviously I have never visited. So, I likely didn’t copy someone else’s mistake. Likely my error was simply my own. So much of MLK’s history took place in Montgomery AND King protested injustice in there, I likely transposed in my mind Montgomery for Memphis and the error slipped by me! No one’s perfect and we all make mistakes. In this case, I simply wrote down the wrong city. Statements are accepted a true but upon careful investigation, the facts reported are wrong.

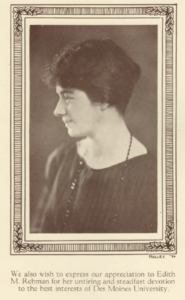

T.T. Shields is a case in point. Many today think that Shields had an affair with his secretary Edith Rebman. The accusation was made in 1929, partly because Shields and Rebman were at a Des Moines University meeting in Waterloo, IA and happened to be in adjoining hotel rooms. The enemies of Shields (possibly Harry Wayman, president of Des Moines U with whom TT was having conflict over Wayman’s bogus academic bona fides) floated the possibility of the affair to the Des Moines board which ultimately exonerated them after a lengthy meeting. Nevertheless, the damage was done, and rumors of the alleged affair appeared in newspapers far and wide. What didn’t appear in print far and wide was the testimony of the hotel in which the alleged affair allegedly took place. While it was true that they had adjoining rooms, the room choices were assigned by hotel staff and had not been requested by either Shields or Rebman. In fact, according to hotel staff, if they had requested such an arrangement, they would have been told that it was not possible. The rooms had already been assigned and those assignments couldn’t be changed. This same situation happened to Shields/Rebman twice in 1929. In Waterloo, IA, at the Hotel Russell-Lamson and in Buffalo, NY at the Hotel Touraine. In both cases, hotel staff selected the rooms which happened to be adjoining simply because they were in the same party, not because of a tryst they wished to enjoin. But as is often the case, news of a rumor spreads far and wide, while the news of the correction is often not passed on. (There is independent newspaper corroboration of these details if anyone wishes to contact me.)

T.T. Shields is a case in point. Many today think that Shields had an affair with his secretary Edith Rebman. The accusation was made in 1929, partly because Shields and Rebman were at a Des Moines University meeting in Waterloo, IA and happened to be in adjoining hotel rooms. The enemies of Shields (possibly Harry Wayman, president of Des Moines U with whom TT was having conflict over Wayman’s bogus academic bona fides) floated the possibility of the affair to the Des Moines board which ultimately exonerated them after a lengthy meeting. Nevertheless, the damage was done, and rumors of the alleged affair appeared in newspapers far and wide. What didn’t appear in print far and wide was the testimony of the hotel in which the alleged affair allegedly took place. While it was true that they had adjoining rooms, the room choices were assigned by hotel staff and had not been requested by either Shields or Rebman. In fact, according to hotel staff, if they had requested such an arrangement, they would have been told that it was not possible. The rooms had already been assigned and those assignments couldn’t be changed. This same situation happened to Shields/Rebman twice in 1929. In Waterloo, IA, at the Hotel Russell-Lamson and in Buffalo, NY at the Hotel Touraine. In both cases, hotel staff selected the rooms which happened to be adjoining simply because they were in the same party, not because of a tryst they wished to enjoin. But as is often the case, news of a rumor spreads far and wide, while the news of the correction is often not passed on. (There is independent newspaper corroboration of these details if anyone wishes to contact me.)

So Shields is tainted with a suspicion of infidelity, although there was absolutely no credible evidence presented. Historians with a natural dislike for TT Shields disparage him by calling Rebman “his purported paramour,” a scandalous slur given the paucity of actual evidence to support it and given that the hotel in question is on public record explaining the situation. An error has been repeated and repeated. How sad. Could Shields have had an affair with Rebman? It’s certainly possible. I have a copy of a letter from WB Riley, courtesy of David Elliott, “Studies of Eight Canadian Fundamentalists” (PhD diss, University of British Columbia, 1989) in which Riley was concerned that there may have been more to their relationship but nothing of substance has ever been discovered. Did they have a relationship? No clear evidence, so no relationship. Just because we don’t like the guy, this doesn’t give us the right to believe a slanderous accusation without evidence. I recently wrote to an author who called Rebman Shields’ paramour and his excuse was that he simply used a few published sources. Too bad he didn’t do real research before he slandered Shields.

Yes, errors do make it into academic writing, for a variety of reasons. Some are simple to explain, others are more difficult. Some errors are easily corrected while others do serious damage to someone’s credibility, even those long dead. Slandering someone who is deceased is no less evil than slandering a living person. Our duty is to the facts . . . just the facts—the good, the bad and even the ugly. But let’s not make them uglier than they really are. Soli Deo Gloria!

Good article. This is why “due process” is necessary before making accusations or inferences.

Excellent, excellent, excellent!

This is an excellent introduction to good historiography! Misquoting, quoting misquotes, confusing sources, and biases we all have. Wow!

The Squire name phenomenon is something I discovered trying to untangle the many Herods in 1st century Israel and Agrippas in 1st century Rome!

Thank you!

RLW