Learning to

Number Our Days

Grieving for Ukraine

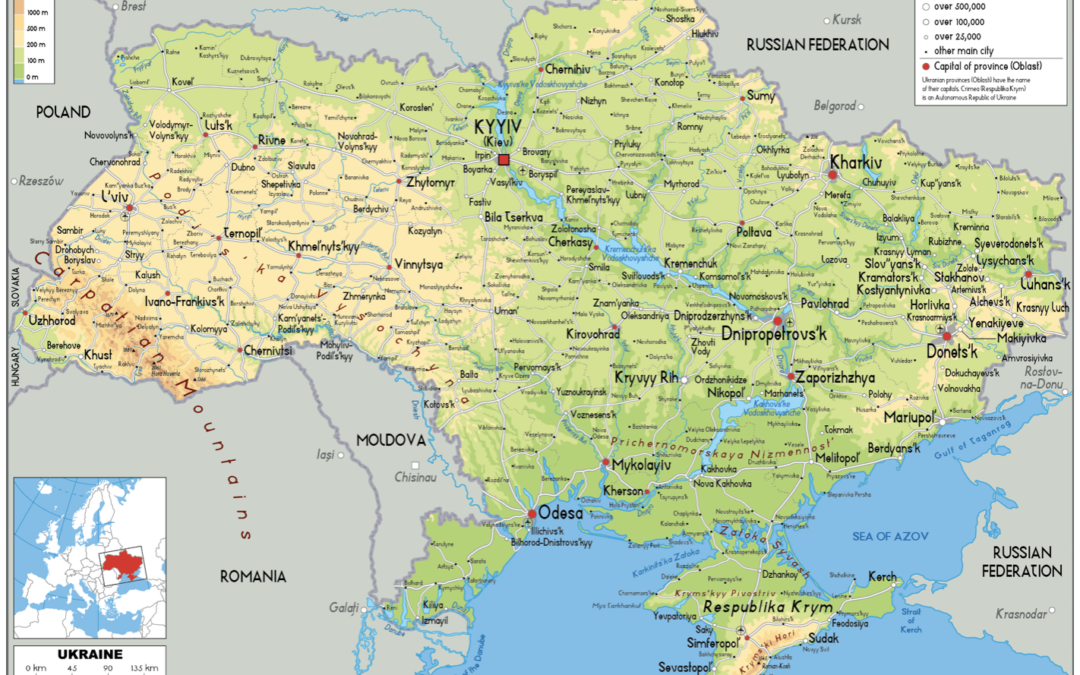

I have been to the Ukraine twice, teaching students and preaching in churches. I have walked the streets of Kyiv, broken bread with believers there and elsewhere in the Ukraine, witnessed the work of God in the country and seen its beauty. I stood on the banks of the Dnieper River where Vladimir the Great in 988 had his subjects baptized into Christianity, marking their official break with paganism. Regardless of what one may think of this mass baptism, today there is a robust evangelical movement in the country led by many fine men and women, some of whom suffered under the old Communist regime, though now they are aged. Younger brothers and sisters have risen to the occasion, trusted Christ and sought theological education so that they may evangelize and disciple their country men and women.

I have been to the Ukraine twice, teaching students and preaching in churches. I have walked the streets of Kyiv, broken bread with believers there and elsewhere in the Ukraine, witnessed the work of God in the country and seen its beauty. I stood on the banks of the Dnieper River where Vladimir the Great in 988 had his subjects baptized into Christianity, marking their official break with paganism. Regardless of what one may think of this mass baptism, today there is a robust evangelical movement in the country led by many fine men and women, some of whom suffered under the old Communist regime, though now they are aged. Younger brothers and sisters have risen to the occasion, trusted Christ and sought theological education so that they may evangelize and disciple their country men and women.

My heart is heavy with the recent news. After weeks and months of posturing, Vladimir Putin ordered Russian troops into the Ukraine this week. He did not want Ukraine to join NATO. As a member of NATO, the west could not have just stood by and watched Putin’s troops roll into the country. Putin’s agenda for a long time was to make the Ukraine a part of Russia. In 2014, Russian troops entered and took the Crimea in southern Ukraine, laying claim to it as historically Russian territory, whether it was or not. Now Putin’s forces are closing in on Kyiv. For those with historical perception, we are witnessing another Hitler marching into the Sudetenland all over again. In 1938, Adolf Hitler, under the pretext of uniting a part of Germany back with the motherland rolled into an area of Czechoslovakia without firing a shot. Of course, there is a principal difference between what we are seeing now and what we saw then—the Ukrainians are fighting back. Another principal comparison to what happened in 1938 is the posture of appeasement by Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister and others. American president Joe Biden, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau and others are issuing sanctions against Russia and Putin, limiting financial opportunities, seizing assets, attempting to intimidate Putin into backing down. This seems unlikely to provide the necessary incentive for him to order the troops home, to suddenly leave the country. This has been a long time in coming, and Putin was ready. Not so much the west.

My heart is heavy with the recent news. After weeks and months of posturing, Vladimir Putin ordered Russian troops into the Ukraine this week. He did not want Ukraine to join NATO. As a member of NATO, the west could not have just stood by and watched Putin’s troops roll into the country. Putin’s agenda for a long time was to make the Ukraine a part of Russia. In 2014, Russian troops entered and took the Crimea in southern Ukraine, laying claim to it as historically Russian territory, whether it was or not. Now Putin’s forces are closing in on Kyiv. For those with historical perception, we are witnessing another Hitler marching into the Sudetenland all over again. In 1938, Adolf Hitler, under the pretext of uniting a part of Germany back with the motherland rolled into an area of Czechoslovakia without firing a shot. Of course, there is a principal difference between what we are seeing now and what we saw then—the Ukrainians are fighting back. Another principal comparison to what happened in 1938 is the posture of appeasement by Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister and others. American president Joe Biden, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau and others are issuing sanctions against Russia and Putin, limiting financial opportunities, seizing assets, attempting to intimidate Putin into backing down. This seems unlikely to provide the necessary incentive for him to order the troops home, to suddenly leave the country. This has been a long time in coming, and Putin was ready. Not so much the west.

Putin thinks that Russia and the Ukraine should be reunited . . . They do have a shared history which is certainly complicated. Nevertheless, does a group of people, 44 million strong, have the right of self-determination? It is not like Ukrainians are welcoming Russian troops into their country with open arms. While some Russian Ukrainians might welcome the military action, most are resisting this aggression, with guns, Molotov cocktails, at times paying the ultimate cost, the destruction of their homes and death to their persons.

Putin thinks that Russia and the Ukraine should be reunited . . . They do have a shared history which is certainly complicated. Nevertheless, does a group of people, 44 million strong, have the right of self-determination? It is not like Ukrainians are welcoming Russian troops into their country with open arms. While some Russian Ukrainians might welcome the military action, most are resisting this aggression, with guns, Molotov cocktails, at times paying the ultimate cost, the destruction of their homes and death to their persons.

What does the future hold for Ukraine? Unless God intervenes, Russia seems poised to enter Kyiv and topple the legitimately elected government. President Volodymyr Oleksandrovych Zelensky is a wanted man who seems likely to have a price on his head. Even if he flees the country for reasons of self-preservation (who could blame him, but today he said he needed ammunition, not a ride!), his career as president may be headed for a very sudden end. Sanctions will not stop what is happening. What will? Will military action? Just over seventy-five years ago, the world saw the end of the last global conflict. Deaths are estimated at 75–80 million or 3% of the global population in 1940, estimated at 2.4 billion. Today, we stand on the precipice of another global conflict. As the world saw with Adolf Hitler, the only thing that might stop Putin is overwhelming military superiority.

Yet with the threat of the use of nuclear weapons, this will be a last resort. Hitler was a bully who had to be taught a lesson. Will Putin be the same? It’s beginning to look like he will. How should believers respond to the current crisis? What can we do? What should we do?

Let me offer some suggestions. You may think of others.

Let me offer some suggestions. You may think of others.

- Recognize that proceeding the coming of Christ, there will be wars and rumors of wars. Remember Matt 24:6 “And you will hear of wars and rumors of wars. See that you are not alarmed, for this must take place, but the end is not yet.” (ESV)

- Pray for our brothers and sisters affected—both in Ukraine and in Russia. Things may get very difficult for them. Prayer is the least we can do. Pray for them individually that God would protect them. Pray for them corporately that God will give them strength to be a witness. Pray for their children, often casualties of war; pray for the women who may be brutalized by their oppressors. Pray for the men who will be called up for military service. One of my Ukrainian brothers has a church on a military base. His wife was my translator during my first visit there in 2003. He may see his entire congregation wiped out in military action. Pray for the pastors to have wisdom to know how to shepherd their flocks during these diffic

ult times.

ult times. - Pray for our own political leaders. Will they take us to war? Should they take us to war? It could happen. Maybe it should if sanctions do not work. Our leaders need divine guidance, even if they do not know the Lord. The king’s heart is in the Lord’s hand. Prov 21:1

- Pray for the Ukrainian political leaders—esp. President Zelensky.

- Pray for Russia and Putin . . . God could deal with him as he dealt with Nebuchadnezzar. He could repent. Pray for those who surround him. He is not alone in this tyranny.

- Pray for world leaders—Boris Johnson, Justin Trudeau, Emmanuel Macron, Olaf Schultz, and others. It may take a united effort to bring this tyranny to an end.

- Pray for the stability in neighboring countries. Romania, once under the Soviet thumb, is receiving refugees now. Christians there are ministering as they are able. Maybe we can help them!

- Pray for a harvest of souls—among the Ukrainians, esp.

- Pray for the mission agencies that help the Ukrainian churches. One agency with which I am familiar is heavily invested in both countries. Things may look significantly different in the days ahead.

- Pray for the soon coming of Jesus Christ. He is the only one who can set this world straight and bring lasting peace.

May God be merciful! We need God now more than ever! Even so, come Lord Jesus!

Christians and Suicide – Do I Have the Right to Choose the Timing of My Own Death?

Over the last few weeks, I have been finishing a series of essays, longer and shorter, that will constitute entries for a new dictionary of Christian history under construction. My initial forty essays were submitted last Tuesday, and I heard almost immediately from the editor about writing some additional entries by the end of the month. I have begun the process and one topic—suicide—I consider this week on my blog. Below is the entry I have written as it now stands. I still have a couple of weeks for revision, but my word limit is about 500 words. Obviously so much more could be said. As with my entry on MLK Jr from several weeks ago, this is a work in progress, and as I was editing this last night, I thought I would address this important topic on my blog for several reasons.

First, we live in a world filled with despair and one recognized alternative to ending the despair is terminating one’s life—suicide. It can take many forms, but the goal is always the same—the end of life and its suffering. Suicide is real and constantly being studied to determine how to curtail its practice. According to one recent report, suicide rates in the US were down by 3% from 2019 to 2020. While the suicide rate declined minimally, there were still nearly 46,000 suicides in the US in 2020. A second reason to consider suicide on my blog is the issue of euthanasia and assisted suicide, now expanding around the world. In 2016, Canada, our home for 19 years, passed Bill C-14 permitting medical assistance in dying (MAID). Last March, Bill C-7 expanded MAID to permit “euthanasia for those whose psychological or physical suffering is deemed intolerable and untreatable.” This is frightening. Suicide is irreversible. Once chosen, there is no going back. Third, ministry individuals are choosing suicide as a way out of their troubles. Recent examples are tragic. Also here and here. I have known several men who committed suicide over issues of sin. One man, a leader among his peers, led a double life that was about to be exposed. The other, an area pastor with whom I had some relationship, chose suicide when his sin was about to be made public through his arrest. The suicide prevented that arrest, but in its wake, left havoc, devastation, immense sorrow for his family, and lots of questions. Fourth, even if ministry leaders don’t commit suicide, they often experience it close to home. I know one man whose wife committed suicide, another who had a son die at his own hand. And well-known CA pastor Rick Warren also lost a son to suicide. How could a Christian commit suicide? How could a pastor? Was he even a believer? What hope is there for me if pastors commit suicide?

Below is my entry (minus the hyperlinks) followed by some concluding remarks. I welcome feedback.

Suicide, death by one’s own hand or actions; self-killing. There are examples in the Bible depicting suicide, the most prominent of which is Judas who hung himself after betraying Jesus (Matt 27:5). Old Testament examples include Abimilech who instructed his armor bearer to kill him with a sword (Judg 9:52–54); Ahithophel who hung himself after the rejection of his counsel (2 Sam 17:23); Israelite king Zimri who burned his house down with him inside (1 Ki 17:18); Saul who fell on his sword followed by his armor bearer (1 Chr 10:5); and Samson who died when he brought the building down killing his enemies (Judg 16:30). Christians debate whether Samson’s death should be called suicide since it was a death in a conflict with Israel’s enemies and God blessed his action. It is significantly different from the story of Judas, who killed himself over his own treachery. Some have even suggested that Jesus’ death was a suicide since he willingly chose a path that led to his demise.

Many Christians view suicide as “self-murder.” If murder is the willful killing of another human, capital punishment and war excepted, then the willful killing of one’s own person would be self-murder and a violation of the sixth commandment, “Thou shalt not kill” (KJV), “You shall not murder” (ESV). Nevertheless, debating the entailments of suicide raises problems for many believers.

From the earliest days of Christianity, Christians have grappled with suicide. A Donatist extremist group of the 4th century, the Circumcellions, had adherents who provoked Roman soldiers or others to kill them that they might become martyrs. However, Christians opposed self-murder from the beginning. Augustine (354–430) in City of God rejected suicide vigorously, even in cases where no other sin occured, such as a woman ravished who bore shame from the act but no guilt from sin. “It is not without significance, that in no passage of the holy canonical books there can be found either divine precept or permission to take away our own life, whether for the sake of entering on the enjoyment of immortality, or of shunning, or ridding ourselves of anything whatever. Nay, the law, rightly interpreted, even prohibits suicide, where it says, ‘Thou shalt not kill’” (City of God, 1, 20). Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) followed Augustine on suicide (Summa Theologica II, II, Q. 64) and both suggested that Samson’s death, while technically a suicide, was justified by God since he enabled Samson to do what he did (City of God, 1, 21).

Roman Catholicism has been strong in its rejection of suicide as acceptable for a Christian, punishable by eternal damnation in most cases as a mortal sin, often leading to the denial of a Christian burial. In the current Catechism of the Catholic Church, suicide is “contrary to the moral law,” but provision is made for mitigation for those who commit suicide under extreme conditions. “Grave psychological disturbances, anguish, or grave fear of hardship, suffering, or torture can diminish the responsibility of the one committing suicide” (CCC, 2282). Since Vatican II, denial of Christian burial has been applied infrequently.

There are two additional difficult questions for believers to consider which ultimately relate to each other. Can a genuine believer commit suicide? (Also, here.) Or put another way, is suicide evidence that the one who commits it was lost? A second question raised, is suicide the “unpardonable sin”? Suicide is irreversible. Counseling should be sought and hope in God offered. The discussion on Christians and suicide is particularly relevant with the increasingly common practice of euthanasia, terminating the life of an individual with an incurable disease, or ending the life of someone who simply wishes to die. Euthanasia goes together with assisted suicide, helping someone terminate their life for whatever reason.

What can the church and believers do about suicide? Obviously, believers are called upon to minister to those left behind when a suicide occurs. Great care must be offered as the grief involved is deep and will be lasting. Beyond what is done after the fact, the subject of suicide needs to be a part of our preaching and pastoral care before is occurs. In pastoral care, someone may express a desire to commit suicide. These threats should not be taken lightly. Intervention may be a first priority. What is contributing to these feelings? How can we help the individual involved?

More broadly, we should address suicide from our pulpits, directly or indirectly. We need to write about it, talk about it, pray about it, and seek to mitigate it where ever possible. This is a good start. What are its causes and what are its cures? Why do believers consider it? How can we mitigate its potential practice among our congregation? People need to know there is hope in Christ. “My hope is in the Lord!”

Getting the Facts Straight

Remember old Sergeant Joe Friday (played by Jack Webb) of Dragnet? He was famous for saying to a witness, “All we want are the facts, ma’am!” Joe the detective, like Jeff the historian, is after the facts. While historians reflect on things like causation—why was Archduke Ferdinand murdered and was his death the contributing factor to the beginning of World War 1?—the facts of the story are of primary importance for the historian because, without them, the interpretation of the events will suffer.

Last week, shortly after I published my essay on MLK Jr., I was alerted to an error in my post by a keen-eyed reader. I wrote that King was murdered in Montgomery, AL, when he was actually murdered in Memphis, TN. I immediately corrected the error on the blog but not before the essay was forwarded to my list of readers. Ugh!!! How did that happen? Talk about a major blunder! There are two major issues that writers seek to avoid—plagiarism, using another’s work improperly; and errors, misstating the details. I committed the latter.

Just how this mistake crept into my prose, I am not quite sure. I had written an entry on MLK Jr. for a new dictionary of Christian history that I am contributing to and, somehow, I made that error in the essay. Did I copy the error from one of my sources? Or did I just get confused in my mind with events in King’s life that happened in Montgomery vs. what happened in Memphis. I am not what you would call a “King scholar,” but his life does create a certain fascination for me, particularly as I have worked on Baptists and race. I had the opportunity to visit the MLK site in Atlanta a few years ago and tour the church. Very important landmarks. But I’ve never been to Memphis (or Montgomery for that matter). I’m sure there are equally important landmarks in those places that highlight the King story. I know that the Lorraine Motel is one such place.

Getting the facts wrong is easy to do, especially for historians. Facts are our burden, our stock and trade. Ferreting out the fine details of a story is part of our craft. Coming up with corrections in the historical record is part of what we do. In some sense, we are always trying to set the record straight, especially in our own writing. No one wants to put something in print that is later proven to be factually in error. Mistakes do happen, hopefully to others but to me? Yea, they even happen with me. Unfortunately.

As historians, we remember when we discover through reading the significant factual errors in another writer’s work. It happens to the best of us. A number of years ago, I was asked to write an essay on Squire Boone, the brother of the legendary Daniel Boone. I was told he was an important Kentucky Baptist. Would I write a biographical essay on his life? Sure. I was sent a box of material that the editor of the series the essay was to be published in had collected on Boone and began my work. Writing on the Boone family is challenging. Daniel Boone is an important figure in American history and there’s a society of Boone descendants that keeps his memories alive. As I began to assemble a narrative on Squire, I learned that the father of Daniel and Squire was a Squire also as was a nephew, the son of a different brother of Daniel. I would eventually learn that there are no less than thirty-two Squires in the Boone genealogy. Keeping them straight was a challenge. To complicate matters, the nephew Squire was a Baptist. Anyway, I eventually wrote an essay that Kentucky Baptist history had wrongly considered Squire, the brother of Daniel, an early Baptist preacher in the state. I argued that the uncle and the nephew had their stories conflated in the historical record. Once one historian of note confused the two, later historians repeated the error, or so I surmised. You’d have to read the essay to see the evidence, but I made a pretty good case for correcting KY Baptist history.

Another error I discovered was in a book that attributed Strong’s Concordance to the Baptist Augustus Hopkins Strong rather than to the Methodist James Strong. It was a surprising error and easily corrected. Not I’m sure how or why my brother historian made the error, but made it he did. Generally, to correct errors such as these, authors need informed readers to read the work and point out the errors to their authors before they are printed. This is often the role of editors and outside readers. Or perhaps some other friend or colleague may be invited to read the text and will note the mistake. I appreciate the brother who alerted me to my error.

So why do errors creep into texts of even trained, careful historians? Let me suggest several reasons why I have seen errors in my own writing and that of others. First a historian is only as good as his sources. Sometimes the sources themselves contain errors and sometimes they are merely vague or spotty and the historian makes a judgment as to proper conclusions. In today’s internet world, access to a diversity of sources offers a much greater opportunity to cross check facts and compare details. Sources that were inaccessible to the researcher without travel or depending on interlibrary loan, can now be located through a variety of online websites—Google Books, Archive.org or HathiTrust.org—plus any number of narrow collections on particular topics. The quality of research today has been significantly improved from just a quarter of a century ago.

In the case of the location of the MLK murder, there is a plethora of material online that specifically notes the location of the sad act. There is even a museum located at the Lorraine Motel, which obviously I have never visited. So, I likely didn’t copy someone else’s mistake. Likely my error was simply my own. So much of MLK’s history took place in Montgomery AND King protested injustice in there, I likely transposed in my mind Montgomery for Memphis and the error slipped by me! No one’s perfect and we all make mistakes. In this case, I simply wrote down the wrong city. Statements are accepted a true but upon careful investigation, the facts reported are wrong.

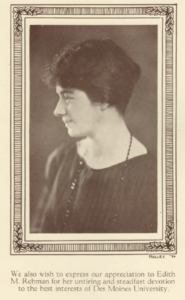

T.T. Shields is a case in point. Many today think that Shields had an affair with his secretary Edith Rebman. The accusation was made in 1929, partly because Shields and Rebman were at a Des Moines University meeting in Waterloo, IA and happened to be in adjoining hotel rooms. The enemies of Shields (possibly Harry Wayman, president of Des Moines U with whom TT was having conflict over Wayman’s bogus academic bona fides) floated the possibility of the affair to the Des Moines board which ultimately exonerated them after a lengthy meeting. Nevertheless, the damage was done, and rumors of the alleged affair appeared in newspapers far and wide. What didn’t appear in print far and wide was the testimony of the hotel in which the alleged affair allegedly took place. While it was true that they had adjoining rooms, the room choices were assigned by hotel staff and had not been requested by either Shields or Rebman. In fact, according to hotel staff, if they had requested such an arrangement, they would have been told that it was not possible. The rooms had already been assigned and those assignments couldn’t be changed. This same situation happened to Shields/Rebman twice in 1929. In Waterloo, IA, at the Hotel Russell-Lamson and in Buffalo, NY at the Hotel Touraine. In both cases, hotel staff selected the rooms which happened to be adjoining simply because they were in the same party, not because of a tryst they wished to enjoin. But as is often the case, news of a rumor spreads far and wide, while the news of the correction is often not passed on. (There is independent newspaper corroboration of these details if anyone wishes to contact me.)

T.T. Shields is a case in point. Many today think that Shields had an affair with his secretary Edith Rebman. The accusation was made in 1929, partly because Shields and Rebman were at a Des Moines University meeting in Waterloo, IA and happened to be in adjoining hotel rooms. The enemies of Shields (possibly Harry Wayman, president of Des Moines U with whom TT was having conflict over Wayman’s bogus academic bona fides) floated the possibility of the affair to the Des Moines board which ultimately exonerated them after a lengthy meeting. Nevertheless, the damage was done, and rumors of the alleged affair appeared in newspapers far and wide. What didn’t appear in print far and wide was the testimony of the hotel in which the alleged affair allegedly took place. While it was true that they had adjoining rooms, the room choices were assigned by hotel staff and had not been requested by either Shields or Rebman. In fact, according to hotel staff, if they had requested such an arrangement, they would have been told that it was not possible. The rooms had already been assigned and those assignments couldn’t be changed. This same situation happened to Shields/Rebman twice in 1929. In Waterloo, IA, at the Hotel Russell-Lamson and in Buffalo, NY at the Hotel Touraine. In both cases, hotel staff selected the rooms which happened to be adjoining simply because they were in the same party, not because of a tryst they wished to enjoin. But as is often the case, news of a rumor spreads far and wide, while the news of the correction is often not passed on. (There is independent newspaper corroboration of these details if anyone wishes to contact me.)

So Shields is tainted with a suspicion of infidelity, although there was absolutely no credible evidence presented. Historians with a natural dislike for TT Shields disparage him by calling Rebman “his purported paramour,” a scandalous slur given the paucity of actual evidence to support it and given that the hotel in question is on public record explaining the situation. An error has been repeated and repeated. How sad. Could Shields have had an affair with Rebman? It’s certainly possible. I have a copy of a letter from WB Riley, courtesy of David Elliott, “Studies of Eight Canadian Fundamentalists” (PhD diss, University of British Columbia, 1989) in which Riley was concerned that there may have been more to their relationship but nothing of substance has ever been discovered. Did they have a relationship? No clear evidence, so no relationship. Just because we don’t like the guy, this doesn’t give us the right to believe a slanderous accusation without evidence. I recently wrote to an author who called Rebman Shields’ paramour and his excuse was that he simply used a few published sources. Too bad he didn’t do real research before he slandered Shields.

Yes, errors do make it into academic writing, for a variety of reasons. Some are simple to explain, others are more difficult. Some errors are easily corrected while others do serious damage to someone’s credibility, even those long dead. Slandering someone who is deceased is no less evil than slandering a living person. Our duty is to the facts . . . just the facts—the good, the bad and even the ugly. But let’s not make them uglier than they really are. Soli Deo Gloria!

Reflections on Martin Luther King Jr.

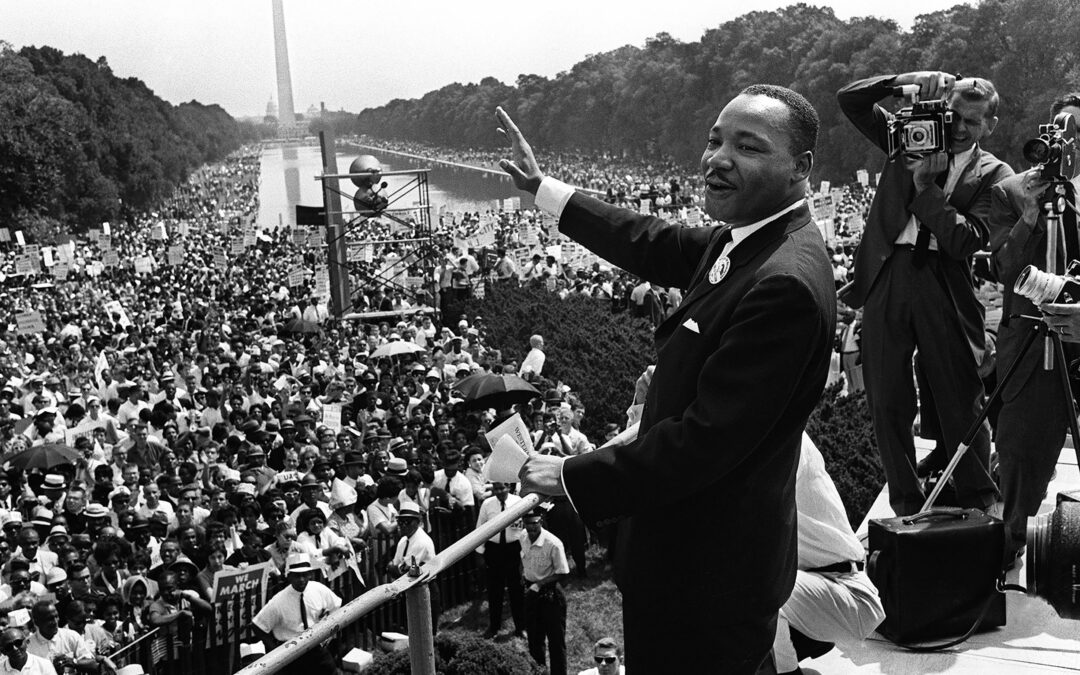

I mentioned last week that I was working on a writing project for a new dictionary of Christian history. One of the entries I was assigned to write was the entry on MLK. Here is that entry

King, Martin Luther Jr. (1929–1968) was an African-American Baptist pastor and Civil Rights leader who was assassinated on 4 April 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee at the Lorraine Motel by James Earl Ray. King had gone to Memphis to aid the Memphis sanitation workers in their strike for better treatment and higher wages.

MLK was born in Atlanta, Georgia, to Michael and Alberta (nee) Williams in 1929. “Daddy King” was an alcoholic sharecropper’s son from rural Georgia who left the farm and came to Atlanta where he eventually met Alberta, the daughter of A. D. Williams, pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church. Michael succeeded Williams at Ebenezer when his father-in-law died in 1931. In 1934, at the behest of the church, Daddy King traveled to Berlin to attend the Baptist World Alliance and came face-to-face with nascent Nazism. He toured Germany during that visit and witnessed the rising threat. Following the trip, King returned to Atlanta and had his name changed to “Martin Luther” after the well-known German reformer. He had his son’s name changed as well. Going forward, they became Martin Luther King, Sr. and Jr.

MLK Jr. was raised in a pastor’s home during the height of the “Jim Crow” south, experiencing the racism commonly directed toward the African American community. Jr. was admitted to Morehouse, the college of both his father and grandfather, in 1944 as a junior in high school, after Morehouse expanded its enrollment to permit younger students who could pass the entrance exams. This was driven by the decreased enrollment due to the need for soldiers during the Second World War. After Jr. graduated in 1948 at the age of 19, he enrolled at the Crozer Theological Seminary, a Northern Baptist school in Upland, Pennsylvania, where he became the student body president. At Crozer, King was introduced to the Social Gospel ideas of Walter Rauschenbusch. Following his graduation from Crozer with his B.D. in 1951, he attended Boston University, where he studied theology under Edgar S. Brightman, who was then promoting Boston Personalism. King graduated with his Ph.D. in 1955, submitting as his dissertation, “A Comparison of the Conception of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Weiman.”

During his doctoral studies, he began his first pastorate at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church of Montgomery, Alabama at the age of twenty-five. Also, he met and married Coretta Scott, a music student at the New England Conservatory of Music 18 June 1953. While pastoring at Dexter Avenue, King led the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955), begun after Rosa Parks (1913–2005), a seamstress and civil rights activist, refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus for a white passenger. King, who was by this time becoming active in the early Civil Rights movement, advocated a position of non-violence, spurred on by the influence of men like Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948). He was arrested after turning himself in and fined $500. It was the first of thirty arrests King would experience during his brief career.

In 1957, King and others formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to help organize black churches to protest civil rights abuses through non-violent means. In April 1963, King was arrested for his 13th time and incarcerated in the Birmingham jail under the supervision of Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor, Commissioner of Public Safety. From jail, King penned “Letter from the Birmingham Jail” which argued that oppressed people had the duty to seek the end of their oppression through non-violence.

A few months later, King was in Washington, D. C. at the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” that saw more than one quarter of a million people attend. At that rally, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream Speech” which became a catalyst for the enactment of the Civil Rights Act (1964). He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize at age 35 in 1964, the youngest man ever to receive this honor, for his promotion of non-violence in the struggle for civil rights. King remained at the forefront of the Civil Rights movement through the next four years, also objecting to the War in Vietnam, delivering a speech, “Beyond Vietnam,” before an audience of three thousand at Riverside Church of New York City. He was controversial, charismatic, and courageous. His life and work are memorialized at a national center, The Martin Luther King Center in Atlanta and at the Ebenezer Baptist Church next door, the church he co-pastored with his father after his departure from Montgomery in 1959.

As can be seen, the entry is brief and offers little commentary. I grew up in the era of Dr. King. I have vague memories of the struggle for civil rights. I have little to no recollection of the churches (Episcopal) I attended during my childhood. Except for one sermon. It was after the death of either MLK or Robert F Kennedy—they died within two months of each other April 4 and June 6, 1968, with MLK killed first. The minister lamented the number of guns he had bought his children over the years, that they could fill the railing around the altar. He proceeded to preach on gun control. I don’t remember what he said, just the occasion for him saying it.

I remember the struggle to make MLK’s birthday a holiday. Many Christians vigorously opposed a day to honor him, especially where I went to university. I had no knowledge of the sensibilities of the school I attended through the 1970s when I went there. I met a fine student who influenced me to attend at a time when my life was largely directionless. I learned much there, and I have great appreciation for the men and women who were my teachers. As with any institution some instructors are better than others, but I had some fine Christian teachers.

However, the school was still struggling with its racist past. I was there when African-American students were first admitted to the student body but with no allowance for interracial dating. I hadn’t been schooled in the issues of racism by then and I can honestly say that while attending, I have few recollections of overt racism, except the color bar for students–we had oriental students when I started just no African American ones. Subtle racism perhaps, but overt? Seldom. As I matured, I entered ministry and went to Canada, to work among the Ojibwe Indians. The racism I encountered there was anti-Indian. There were few blacks living anywhere near where I was. My second ministry was further north in Alberta. More indigenous peoples, few if any blacks. But still plenty of racism.

I encountered white racism against blacks when I returned to the US to pursue my PhD. The Georgia church I attended had few African Americans attending. I didn’t give it much thought as we were in a northern Atlanta suburb that seemed predominantly white. However, in time, a few men in that church let loose with some ugly comments that let me know I was in the deep south. These men were old enough to be my father. I winced at their comments and wish I had said something to rebuke them, but I felt embarrassed to challenge them. Then I came to Minneapolis to teach and heard a respected leader utter a reprehensible racist joke under his breathe while preparing to speak in chapel. I did challenge the man afterwards.

Sadly, racism is ever present with us. Am I a racist? I hope not. Through my teaching career, I was constantly reading and thinking through the material I taught my students. I was also aware of the tensions in the wider evangelical world. Over the years, I made about a dozen trips to Africa to teach African brothers church history. I wanted to be sensitive, so I tried to tailor my notes to reflect their world. I developed a History of Christianity in Africa course. However, my course on Baptist history was almost exclusively a class in white history. Why was this so? There were important African American preachers, many of them former slaves, that left their mark for Christ. Why didn’t I discuss them? I worked to expand my notes.

I said all this to say that today our nation remembers MLK. He was a Baptist. He wasn’t a conservative. I heard once that King wanted to attend a more conservative school but was denied enrollment. He attended Crozer, then under the grip of theological liberalism. He embraced their theology. He also was deeply flawed. In 1991, a panel of Boston U scholars determined he plagiarized in his dissertation. The FBI dogged him as “the most dangerous man in America.” Because he advocated the violent overthrow of his government? Hardly. Just the opposite. They didn’t like his ideas. King left a mark on American history that cannot be ignored. I have often wondered recently how much of the anti-King rhetoric I heard over the years was generated more by racism rather than by a desire for orthodoxy. He was vilified by many professing Christians down through the years. But America’s leaders have all been deeply flawed men and women.

In 1964, my alma mater gave Alabama governor George Wallace an honorary degree. The same George Wallace who the year before when inaugurated as governor of AL stated “I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow and segregation forever!” Between MLK and George Wallace, who was the better man? As an historian, it is my duty to remind us of our history—the good, the bad and the ugly. MLK is an important part of the American story. It is fitting that we remember him today.

Not My Father’s Faith

I’m back. After a two-month hiatus from the blog that saw me concentrating on other writing projects, I am going to be shooting for weekly blog essays on various topics going forward. I am also finishing a writing assignment for a new dictionary of Christian history. Fascinating research about some fascinating topics and individuals, with about a 50/50 split. The essay on Charles Hodge of Princeton reminded me again of what a prodigious scholar and churchman he was. I was supposed to write 500 words about him, but—seriously!!!—500 words is hardly doable! The essay ended up being 650 words, but I am not sure I did him justice! I hope to offer some of these stories in the days ahead on the blog.

However, I recently had a new (old) essay published by the American Baptist Quarterly that is the impetus for this week’s blog. The essay was written more than ten years ago using research I came across when I was given a grant to use the collections of the Rockefeller Archive Center in Sleepy Hollow, New York. The RAC, as you might imagine, is the repository for the archival material of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (1839–1937) founder of Standard Oil and the richest man in history until recently when early last November he lost that eighty year distinction when Elon Musk overtook him, at 340 billion which is what JDR’s fortune was valued when adjusted to inflation. He was also a Baptist layman who fell under the influence of men like William H. P. Faunce (1859–1930), pastor for ten years of what would become Riverside Church. In Sr.’s day, it was Fifth Avenue Baptist Church. Sr. moved his family and his rapidly growing oil business headquarters from Cleveland, Ohio to New York to Fifth Avenue where he attended the church once pastored by Thomas Armitage. Faunce became pastor in 1889, before he went to Brown University in 1899, becoming the president for the next thirty years. He raised the ire of the fundamentalists during the controversy of the 1920s.

However, I recently had a new (old) essay published by the American Baptist Quarterly that is the impetus for this week’s blog. The essay was written more than ten years ago using research I came across when I was given a grant to use the collections of the Rockefeller Archive Center in Sleepy Hollow, New York. The RAC, as you might imagine, is the repository for the archival material of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (1839–1937) founder of Standard Oil and the richest man in history until recently when early last November he lost that eighty year distinction when Elon Musk overtook him, at 340 billion which is what JDR’s fortune was valued when adjusted to inflation. He was also a Baptist layman who fell under the influence of men like William H. P. Faunce (1859–1930), pastor for ten years of what would become Riverside Church. In Sr.’s day, it was Fifth Avenue Baptist Church. Sr. moved his family and his rapidly growing oil business headquarters from Cleveland, Ohio to New York to Fifth Avenue where he attended the church once pastored by Thomas Armitage. Faunce became pastor in 1889, before he went to Brown University in 1899, becoming the president for the next thirty years. He raised the ire of the fundamentalists during the controversy of the 1920s.

As I was working on various collections of Rockefeller material related to the Northern Baptist Convention—Sr. and Jr. were heavy contributors to the NBC, sometimes donating upwards of nine percent of its annual budget—I came across a collection of letters that Augustus Hopkins Strong (1836–1921) wrote to his son Charles Augustus Strong (1862–1940) during the final decade of AHS’s life. The younger Strong had been raised to follow in his father’s footsteps, even studying at the Rochester Theological Seminary where his father was the president and professor of theology. However, Charles went to Harvard after RTS and studied philosophy under William James and became a close friend of George Santayana, with whom he shared a philosophy prize together to study in Europe and maintained a life-long friendship.

The reason the letters were in the RAC was that Charles had married Elizabeth Rockefeller (1866–1906), the eldest child of JDR, Sr. whom Charles met in Cleveland when his father AHS was a pastor. In the absence of JDR’s regular pastor, AHS preached a funeral for a JDR child and the two men—the future theologian and the future oil magnate became acquainted, with their children ultimately marrying. AHS and JDR became “friends” which served the seminary president well as AHS often tapped JDR’s larder for the needs of RTS. The RAC is also the repository of the Charles Augustus Strong papers.

Without telling the full story recounted in the article (read the essay!) the short version is that Charles “lost” his faith and was put under church discipline by the family’s church, Second Baptist of Rochester in 1892. He became an out and out skeptic and never returned to Christianity. In the letters I “discovered” (I am not aware that any AHS scholar has cited from this collection ever!), about four hundred in number spanning about ten years, the elder Strong tried to woo the younger man back to his Christian roots, even going so far as to convince the Second Baptist church to rescind the church discipline without Charles returning to the faith.

It is a tragic story of the abandonment of the faith from one generation to the next. Yet this is hardly an isolated incident. In 2019, I had a similar essay “A Young Man’s Difficulty with His Bible: Not My Father’s Faith” published in Once for All Delivered to the Saints, where I discuss a comparable story—the life of Faunce whose father was orthodox while the son left orthodox Christianity during the ascendancy of theological liberalism among Northern Baptists. The father, Daniel W. Faunce, wrote a series of books about the Bible that seemed to track his efforts to woo his son to return to historic orthodoxy (see the Faunce essay for details).

This brings me to my ultimate purpose in writing this essay this week—a pastor’s greatest heartache is watching his children abandon the Gospel he has labored so long to declare. It has happened again and again—in church history and in contemporary life. I learned recently of a brother whose child informed him of such a departure. In fact, I have a list of children of ministry brothers who have experienced similar personal sorrow for whom I personally pray on a regular basis that they might return to the faith or, in many cases, might be converted. Children who announce to their parents that they no longer believe what they were led to believe as children, may not have lost their faith. They may actually not have possessed it in the first place. Many of these now adult children made “professions” of faith and were duly baptized in their faithful father’s churches by their fathers who were, in turn filled, with great expectations regarding how God might use their children for his glory in future days. Yet in adulthood, out from underneath the watchful eye of their fathers, or perhaps while still living at home, these children walked away from Christianity. Of course, pastors are not the only ones who experience this heartache. Many a fine Christian couple has wept over the departure of a child from Christianity. It is a great sorrow.

The list of sin and depravity that these ministry children engage in need not be rehearsed here. Sometimes, these wayward children do not formally renounce Christianity but practice sinful behavior at variance with their Christian profession. At other times, they announce rather publicly their rejection of Christianity. Of course, the question that is agonized over by my ministry brothers (and their wives) is “Where did I go wrong? How could my son or daughter do this? What did I miss?” Let me say at the outset, that as fathers, we failed our children in many ways. We were too busy, too distracted, too forceful, not forceful enough, too rigid, too lax, too, too, too. Yes, we do soul searching as we should, but we must also remember that it is not a wonder that so many reject Christianity but that so many don’t! The ministry can be hard on our children. Try as we might, we cannot always insulate our children from our own sins or the sins of others. We work constantly to shepherd their hearts toward God. But remember, only God can change the heart of anyone—you, me, and our children. We beg God for his mercy, yet at times, all the pleading in the world seems insufficient to stop what is happening with our children.

This essay is not meant to be one of gloom and despair but one of hope. What can we do when this happens to our children? Our sons and our daughters? What can we do? First, we must remember to love them unconditionally. Our unconditional love, like God’s unconditional love for us, not loving them in their sin but loving them despite their sin, may yet touch their hearts. We also need to pray for them regularly without nagging them. They likely know what we think and have heard it all before, a hundred times. Will rehearsing things over and over really help or will it drive them further away? Look for occasions to slip in gospel truth into conversations without being overbearing. Petition others to pray for them. Petition God to send other messengers to bring His Word to their hearts and minds. As ministry men, we should pray for each other and for each other’s children (and now that I am a grandfather, for our grandchildren). We must hold out hope that the grace of God can reach into the darkest places and shine light. It’s not over until it’s over. May God be merciful to us and to our children. In this ever darkening world, we desperately need his grace and so do our children. God’s purposes will not be thwarted. Can we trust Him with these needs?

What we must not do is what AHS did. At the end of his journey, his regrets over his son’s departure from the faith prompted him to do some bizarre things. He petitioned the Second Baptist Church to repeal the act of church discipline of twenty-five years earlier. The church agreed but this action was taken without Charles ever returning to the faith. AHS tried to convince CAS that he really was a Christian even though there was no evidence or claim to that end. It’s a sad story, made sadder by AHS’s appeal. God be merciful!

ETS 2021. Baptists and Freemasonry

My ETS paper — Baptists and Freemasonry, A Conflicted History. I am reading this in Ft Worth on Tuesday, at 9AM.

Baptists and Freemasonry 11-16